photography

Sociotechnics: tactile technologies

Tactile technologies are fundamental to human culture, rooted in the concept of embodied cognition—the idea that the mind extends into the world through physical interaction. Tools and processes that directly engage our sensorimotor systems have historically shaped how we interact, think, and evolve. The tactile endures because it provides immediate feedback, a sense of agency, and seamless integration with our physical surroundings. Even in today’s fragmented, digital-first world, technologies that tap into our innate capacity for touch and direct manipulation will remain central to the human experience.

Fire (Agni in Sanskrit), in my view, is the quintessential tactile technology. Remarkably, we learned to harness fire around two million years ago—a timespan so immense it defies comprehension. Since then, Fire has been transformed the human condition profoundly and permanently. It has been, and still is, everything from a practical tool and everyday utility, to a profound symbol and a living deity that has shaped our biology, culture, and nature. Fascinated by fire’s enduring presence, I’ve found myself drawn time and again to capture its special place in the human story, like above in my hometown, Hyderabad, India in 2023.

A choreography of weight and balance, an encounter between the human body and the materials of survival in the Garhwal Himalaya in 2004. The carried firewood is not merely a burden but the promise of combustion—a future moment of transformation waiting to unfold. Here, the road is not a path of leisure but a line of negotiation, cutting through the high wilderness with its demands and offerings. Firewood becomes currency, its value shaped by the labor of gathering, the strength of carrying, and the unseen economies of exchange that surround it. The fire itself is absent, but its inevitability looms large—each step she takes is a prelude to the flames that will burn later, bringing warmth, food, and light.

I was drawn to this impromptu gathering of ravers while wandering a beach in Los Angeles in 2006. Coming upon this scene was to step into the raw emotion of a moment where firelight became the pulse of a shared experience. It was not just a moment to witness, but a moment to feel.

In contrast to the continuous, tactile connection inherent in firework and firedance, the digitalised discotheque presents an apparently profound disruption - a tear. Digital seems in many ways a switch from connection to control, from the living and the seamless to the discrete and the modular, often mediated by screens, beams, and a mammoth underlying infrastructure of electrified light. The transition feels sudden, abrupt, yet elevative and energising in its own way. Is this the substitution of the communally shared flame with the algorithmic precision of individuated choreography? Or something just different? Photos above and below taken in Helsinki in 2022.

Despite the rapid proliferation of the electric and the digital instantiations of fire, the living flame itself remains central to us humans, and very much in our midst. One of its enduring presences is in the ritual and act of smoking, below enjoyed leisurely through a shisha in a St. Petersburg bar in 2017, as the night comes in.

A hand-rolled cigarette, it is known, offers a distinctly different smoking experience —an interface of a subtler kind - to that of a machine-produced one. It carries with it the magic of making—a quiet ritual that reintroduces the tactility seemingly lost in modern conveniences. It is no surprise, then, that in this its organic element, the hand roller cigarette serves as a nearly graceful complement to the juicy berry above. Photo from 2014 in Helsinki.

In the act of burning a handmade incense, fire becomes a bridge between the tangible and the transcendental. The smouldering flame, subdued and purposeful, transforms material into fragrant smoke—a delicate offering that rises and dissipates, carrying intention into the unseen. Within this small shrine’s sacred space in the Garhwhal Himalaya, the fire thus tamed is not merely functional; it is symbolic, a conduit for meditation and prayer, for the creation of atmosphere, and an invocation of the divine.

Everything about the presentation, manner and art of this wandering musician in Hyderabad, India in 2023 exudes tactility. It is miraculous that such age-old traditions persist amidst the bustling silicon metropolis the city has become. The instrument, the elaborate clothing, the beloved bull, and the multifaceted performance come together to in a spectacle that embodies the immediacy of the tactile—a visceral reminder of a world rooted in touch, texture, and presence.

The tactile interaction with the instrument offers continuous, real-time feedback, shaping the way musicians learn, express, and communicate through sound. The act of playing an instrument is more than producing sound; it is a rhythmic, dynamic dialogue between the body and the evocative object, a true play of the extended mind. This feedback loop, rooted in the physicality of touch and the manipulation of materials, is what makes organic musical instruments so uniquely human.

Electronic music devices, harnessing an episodic media, are still primarily actuated through tactile interfaces. The fingers of the DJ shape the binary signals into a continuous, tangible orchestration, here at an underground rave in Helsinki in 2022.

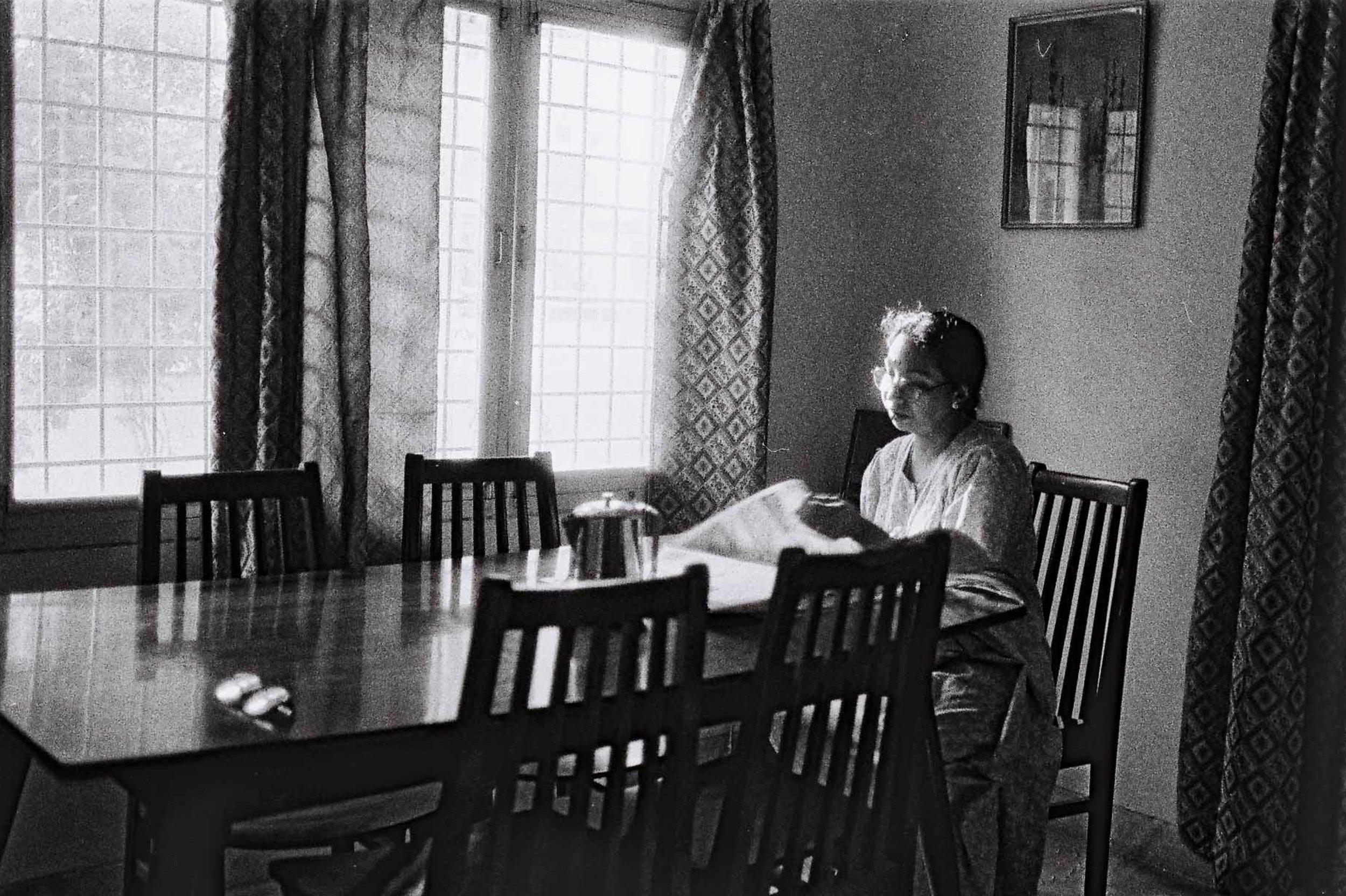

The newspaper has now been relegated to the bottom of the proverbial media shelf, so to speak. Looking back at when the thing was a fixture of the quotidian, it is hard to track the swift and seamless transition to digital media as the primary form of news consumption. The newspaper took space, required space to use, had limits, and did not run on for forever. It had a characteristic smell and a sound. It was immersive and it was curated. I miss the newspaper. Photo from Hyderabad, India, circa 1995-96.

Sculpture is a performance of intimacy, here with both material and model. I enjoyed sitting in on the above sculpting session over a leisurely afternoon circa 2002 in Hyderabad, India.

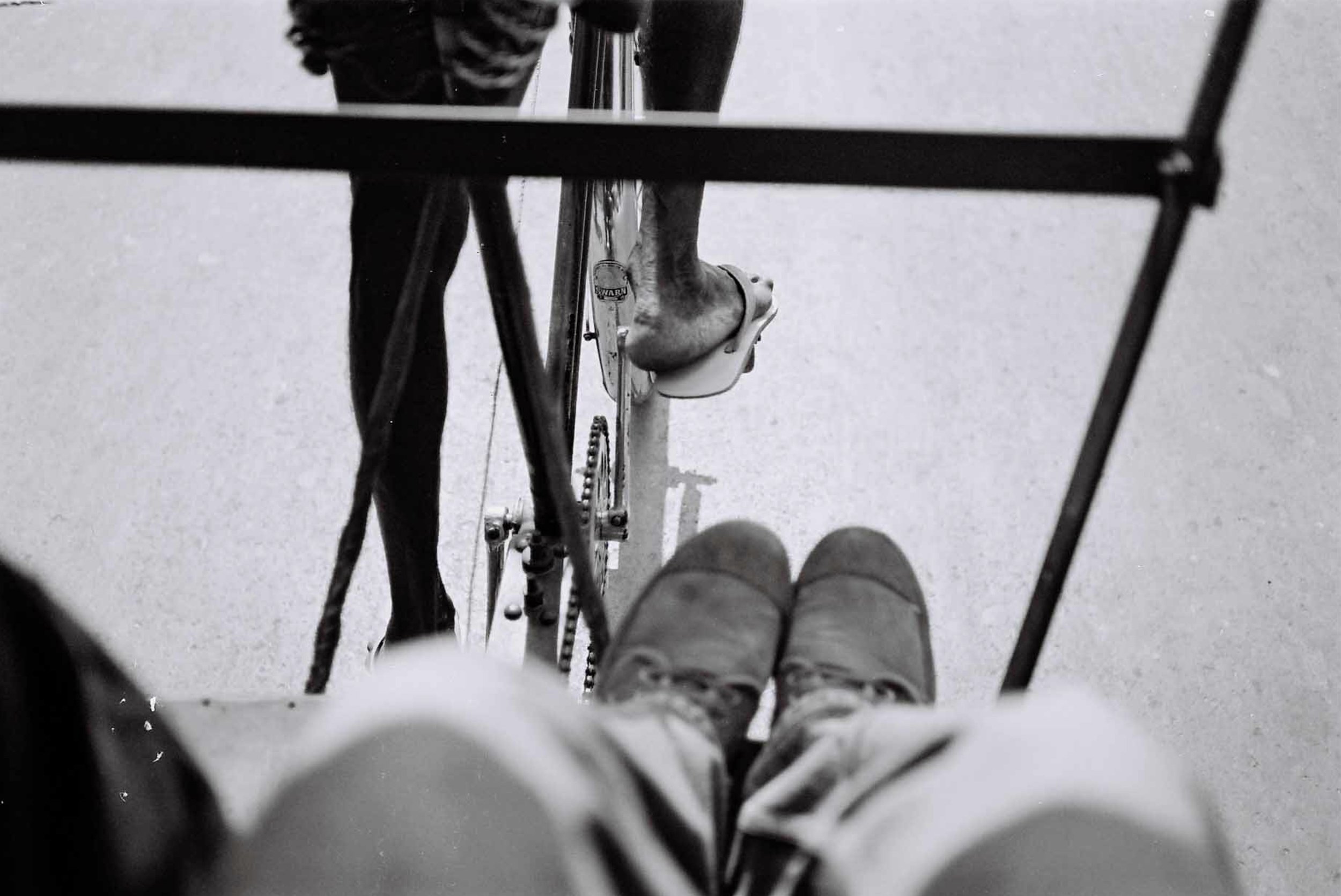

A self-portrait from circa 2004, exploiting an opportunity made possible by the otherworldly instantaneity of the camera.

Sociotechnics: Vehicles

Tactile technologies are fundamental to human culture, rooted in the concept of embodied cognition—the idea that the mind extends into the world through physical interaction. Tools and processes that directly engage our sensorimotor systems have historically shaped how we interact, think, and evolve. The tactile endures because it provides immediate feedback, a sense of agency, and seamless integration with our physical surroundings. Even in today’s fragmented, digital-first world, technologies that tap into our innate capacity for touch and direct manipulation will remain central to the human experience.

Transportation as a service in India used to be a high touch affair. The ‘rickshaw’, a human propelled form of transportation, came with a far more porous boundary between the world outside the vehicle from the one within, compared to deeply hermetic, sealed-off environment that an Uber offers us today. Rickshaw passengers experienced a more direct, continuous contact with the world outside, feeling the sights, sounds, smells, the weather, other passing vehicles, and all of these became essential ingredients of the magical rickshaw experience. It also separated the passenger from the driver (the puller) far less than today. I mean, you really felt the effort when the going was uphill or tough, and the abandon of speeding downhill once a peak was attained. We all participated in a common ride, and when we got off we were more the thankful for it. Photo from somewhere rural in the former state of Andhra Pradesh, circa 2000.

To this day the autorikshaw (a version of the ‘tuktuk’) is a ubiquitous mode of shared transport in India. It retains so many of those elements of tactility and contact with the external environment I’ve alluded to above. Photo Hyderabad circa 2002.

Boats seem to carry a quiet spirit within them. A spirit that speaks of newness and unfamiliarity, of leaving, from terra firma to the really quite unknown and eternally unknowable world of water. Photo Copenhagen 2008.

The sportscar represents an iconic transformation of the personal vehicle from carrier of the physical body to a bearer of the self, a seal of identity. This is the rush of tactile control and continuous feedback on steroids. Photo Helsinki circa 2018.

Interstitials

The threshold. The liminal. The glitch in the matrix. That microsecond between seconds that lasts an eternity. If you find it you may seize it with a camera. And then it might stay with you a long, long time. Attention is the defining element of photography. This is a collection of photos taken, and images made from them, across continents in 15 year span.